The first private space mission to another planet could launch as early as next year, carrying a robotic space probe to Venus to scan its clouds for chemicals essential to life.

The small robotic probe — the first of a planned series of three called the Venus Life Finder missions — is among the most ambitious of a growing slate of planned space missions happening outside not just the traditional government space institutions but also the handful of major companies, most notably SpaceX and Blue Origin, that have dominated the private space industry so far.

“Space is becoming cheaper in general, and there is more access to space than ever before,” said Sara Seager, the principal scientific investigator for the VLF missions and a professor of planetary sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Construction of the probe’s two-pound scientific payload has already begun with funding from MIT alumni, Seager said, while the costs of building, launching and operating the entire 100-pound robotic probe during its mission to Venus will be met by Rocket Lab, an aerospace company based in Long Beach, California

Rocket Lab, like much of the growing commercial space industry, has focused on launching satellites into space. The company has already placed more than 100 satellites into orbit using lightweight rockets launched from New Zealand’s Māhia Peninsula, and plans soon to launch rockets from its new launch complex on Wallops Island in Virginia. A spokesperson for the company declined to answer questions about costs and funding of the VLF mission.

Mason Peck, a professor of astronautical engineering at Cornell University and a space industry expert, estimated it’s likely to cost more than $50 million. And while it’s not yet clear how Rocket Lab could profit, the company could be in line for contracts for other scientific space missions if it successfully operates a probe to Venus, he said.

Although the VLF mission would be the first private probe to another planet, it comes after other signs that private industry is moving into scientific space exploration.

The California-based space fund Breakthrough Initiatives, headed by the Russian and Israeli billionaire Yuri Milner, announced its Starshot project in 2016 (Peck is an adviser on that project). Starshot is an estimated $100 million effort to develop hundreds of tiny light-sail probes that could make the journey to Alpha Centauri, the sun’s nearest star, in about 20 years, instead of the tens of thousands of years that would be needed by the fastest probes that now exist.

Last year Breakthrough Initiatives also announced they’d fund the TOLIMAN project — a small private space telescope to search the Alpha Centauri system for planets, which presumably could be destinations for the Starshot probes.

Robert Jacobson, a space industry analyst and the author of the book “Space Is Open for Business,” said there are similarities between the funding of space missions today and the earliest phases of the exploration of the New World, which were paid for by wealthy monarchs.

“There wasn’t an early business plan. There were a lot of unknowns,” he said. “So even if there’s not yet a business case for Mars, or for Venus … you will start to see business cases for sending [missions] to these other places in the solar system, whether for governments or for the private sector.”

Seager said Breakthrough Initiatives funded an initial study for the VLF missions, but it had no further involvement.

She said the small VLF missions would complement the much larger DAVINCI+, VERITAS and EnVision probes to Venus planned by NASA and the European Space Agency, which will get there in about a decade.

Their main purpose will be to look for signs that Venus had oceans of water in the distant past. That would mean Venus was once a lot cooler and that life may have evolved there, although it would be impossible in the extremely harsh environment that exists there now.

But the VLF probes will be much less expensive than the NASA and ESA probes, which means they can be built quickly and get to Venus much earlier, Seager said.

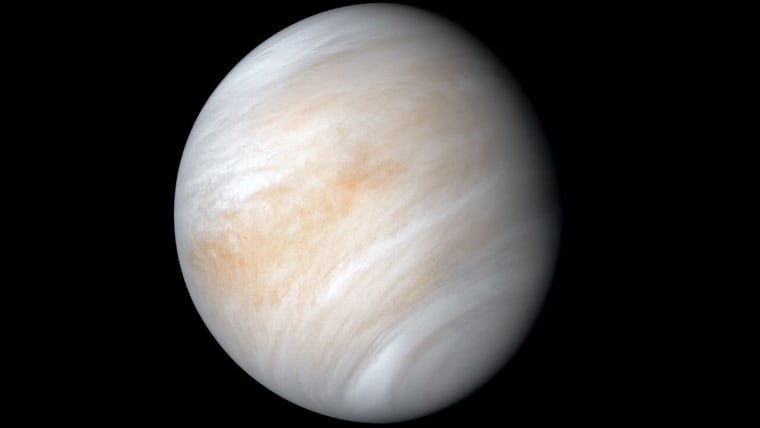

The VLF probes will be designed to search for signs of life in the dense clouds of Venus, about 30 miles above the surface, where it’s cool enough for water to condense — although the clouds are known to be mainly sulfuric acid.

Although Venus is now one of the most inhospitable places in the solar system — the temperature on the surface is hot enough to melt lead, and the pressure of its unbreathable atmosphere is almost 100 times that of Earth’s — some scientists think it’s possible that microbes could survive there by floating in the cloud layer.

That idea was reinforced with the announcement in 2020 that phosphine had been detected in the Venusian clouds — a discovery that was interpreted as a possible sign of microbial life.

That announcement was met with some skepticism, however, with some scientists proposing nonbiological sources of the phosphine, and others suggesting phosphine hadn’t been detected at all.

But the team behind the phosphine detection has doubled down on its claim, saying the phosphine signal it saw is real and that alternative explanations, such as volcanoes on Venus, wouldn’t cause it.

Many of those scientists are now involved in the VLF missions, including Janusz Petkowski, an astrobiologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who’s now the program’s deputy principal investigator.

“The phosphine on Venus is just one of the many anomalies that have been detected in the Venusian clouds over decades,” Petkowski said. “This discovery is just the newest mystery.”

If all goes to plan, the first VLF probe will skim the Venusian atmosphere for three minutes, while scanning the surrounding clouds with a laser.

But the first probe won’t look for phosphine — instead, the on-board laser will be tuned to detect carbon-based chemicals that are considered essential for life, even in highly acidic environments like the Venusian clouds.

A search for phosphine and other anomalous chemicals could be part of later VLF missions, Petkowski said.