For MIT astrophysicist Josh Borrow, he’s just trying to figure out how the universe works

Raider Times photo / Courtesy Josh Borrow

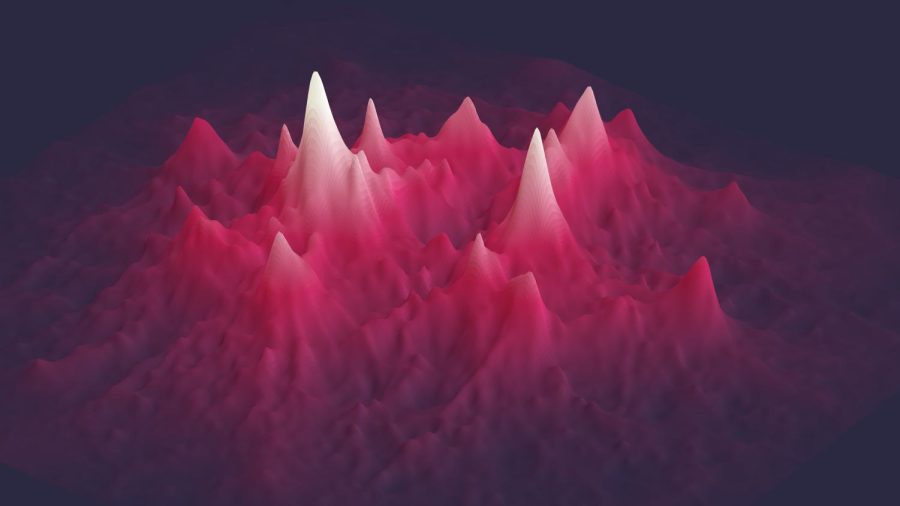

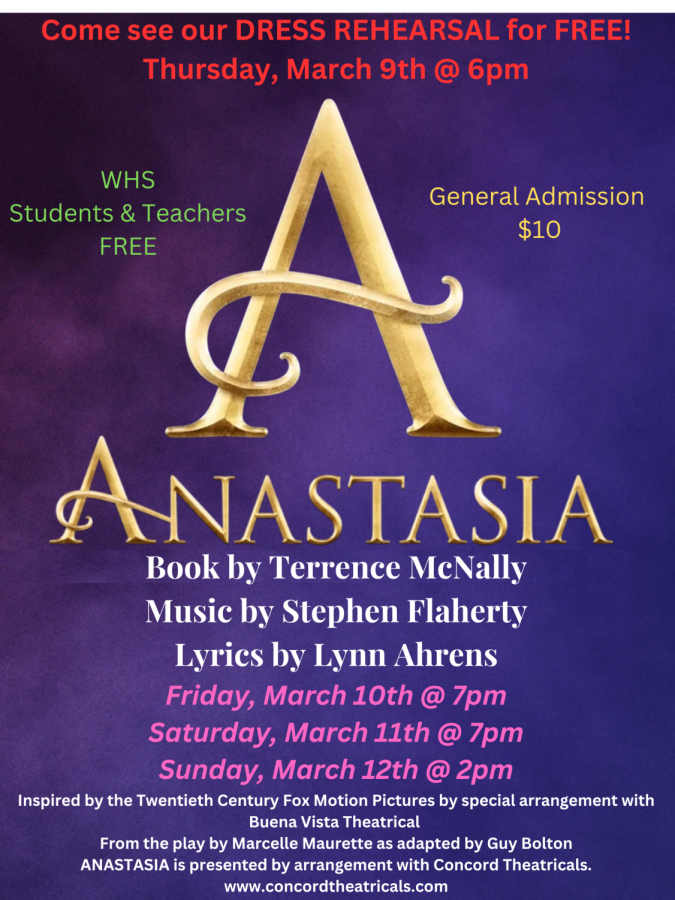

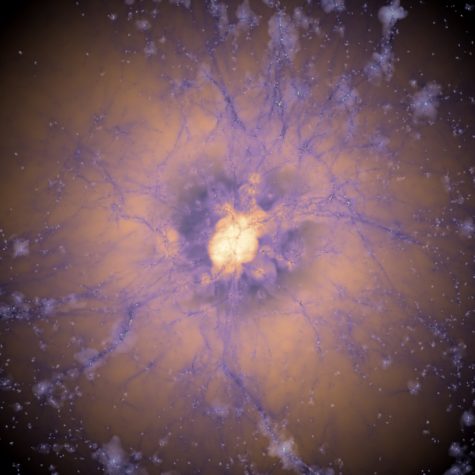

A mountainous structure created by Josh Borrow from a SWIFT cosmological simulation.

March 19, 2022

Have you ever wondered about how exactly scientists discover and research new things and ideas about our universe? How did they figure out how the Big Bang started and how our very own galaxy, the Milky Way, was formed approximately 13.6 billion years ago?

Josh Borrow, an astronomer at MIT, explained how that happens when he recently spoke with the Raider Times over Zoom. Calling in from Brookline, Borrow spoke about his work, the events leading to his chosen profession, and the current leaps in space technology.

Borrow grew up in the northeastern region of the United Kingdom and attended a normal high school where he took various classes in physics, mathematics, and astronomy. He said that he had wanted to be a medical doctor for a while growing up but that would have been a terrible idea to pursue because he hated blood.

“There was this idea when I went to school that if you were good at science, and all these things, you should become a medical doctor, which is a very noble profession, but you need a lot of skills that I definitely don’t have,” he said. “I’m glad I didn’t end up doing that.”

Borrow went on to attend Durham University in the UK where he continued to study physics and eventually get a PhD. I think the most inspiring thing about that is just how small we are relative to the rest of the universe. And yet these small little things are trying to figure out how the universe works. — JOSH BORROW, MIT's Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research

“When I was in school, I enjoyed physics classes. I was like, ‘OK, I will study physics in university.’ And when I went there, I had no idea what I wanted to do!” he said.

At Durham, Borrow organized some science talks where Borrow and anyone who wanted to join would meet and listen to scientists talk.

One of the scientists that made an appearance was Richard Bower, who was a professor at Durham and later went on to be Borrow’s supervisor over the summer. He designed a website for the sole purpose of communicating the research that was happening to the public. He did this web development for some time including in the Netherlands at Leiden University.

After receiving a PHD, Borrow got a job at MIT where he is now a postdoctoral researcher with the Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, and he has designed some software to run galaxy simulations that scientists, including himself, use to study galaxy and star formations.

“The question we are trying to answer is ‘How do they get there and why do they look like that?’ ”

Among Borrow’s accomplishments is a simulating program meant to create computational visualizations and simulations of the particles of the universe. With this, you can see stars and galaxies billions of years ago in hopes of understanding their origins.

Such programs have yielded galaxies and celestial bodies never before dreamed of by human minds. The simulations work by using mathematical equations to show individual particles working together on a scale of billions all at once. This way they can see exactly how things get there and how they move.

“One of the things that comes with this job is this odd sense of scale,” he said. “I think astronomers really understand scale better than many people do. And I think the most inspiring thing about that is just how small we are relative to the rest of the universe. And yet these small little things are trying to figure out how the universe works.”

Most astronomers will use telescopes to do their research, focusing on what they can see with their eyes. But Borrow does most of his research through his computer.

His computer connects to various “supercomputers” that are situated in many locations across the world – like Holyoke, Mass., Texas, Hamburg, Germany, and even one back in Durham. Borrow explained how this was one of the first reasons for the invention of the Internet, to be able to connect to computers all over the world.

“One of the big things that we’ve done is made this very open to the public, so you can download any of the software that we’ve used to run our simulations,” he said.

There was this idea when I went to school that if you were good at science, and all these things, you should become a medical doctor, which is a very noble profession, but you need a lot of skills that I definitely don’t have. I’m glad I didn’t end up doing that.

When asked about how his work inspires him, he said, “One piece of research might come out of a single conversation with somebody, and then you spend the next two years working on something from that five-minute conversation.”

Borrow had never envisioned himself being an astronomer.

“As you can see, it’s really been a stumbling career path,” he admitted.

“In my eyes, if I had set my goal on something I wanted to do in 10 years time while I was in high school, I probably wouldn’t have made it here because a lot of life happens in those 10 years. And so in those 10 years, you have to decide what’s good for you, what you enjoy about what you’re doing now, and where you want to take you next, rather than setting this one linear path for yourself.

“It’s all about getting skills that enrich your livelihood and enrich you.”

Borrow serves an important role in space discovery, figuring out the answers to the questions we lie awake at night thinking about everyday. Where did we come from? How did we get here? Why? Everyday we come closer and closer to those answers.

“You don’t know what impact your work is going to have until 10 years in the future when someone decides to take an observation of something you simulated,” he said.

“I just play a small piece in all of this, but a house of cards is made out of individual cards I suppose, and if you don’t have one of them, the whole thing falls down.”

(For more information about Josh Borrow and his work, go to his website, www.joshborrow.com. For information about MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, go HERE.)

(Story reported and written by Abby Hendrick, Adelle Sheynkman, Adrian Schick, Adrianna Williams, Dayana Posada, Fathima Perez-Cordero, Gina Rank, Izzy DeLorio, Jenna Atiyyat, Leanna Dorian, Liliana Souza, Maria Vasques, Nabila Abenaou, Rylee Valstyn, Toria Dicker, and Valerie Duong.)

–March 19, 2022–