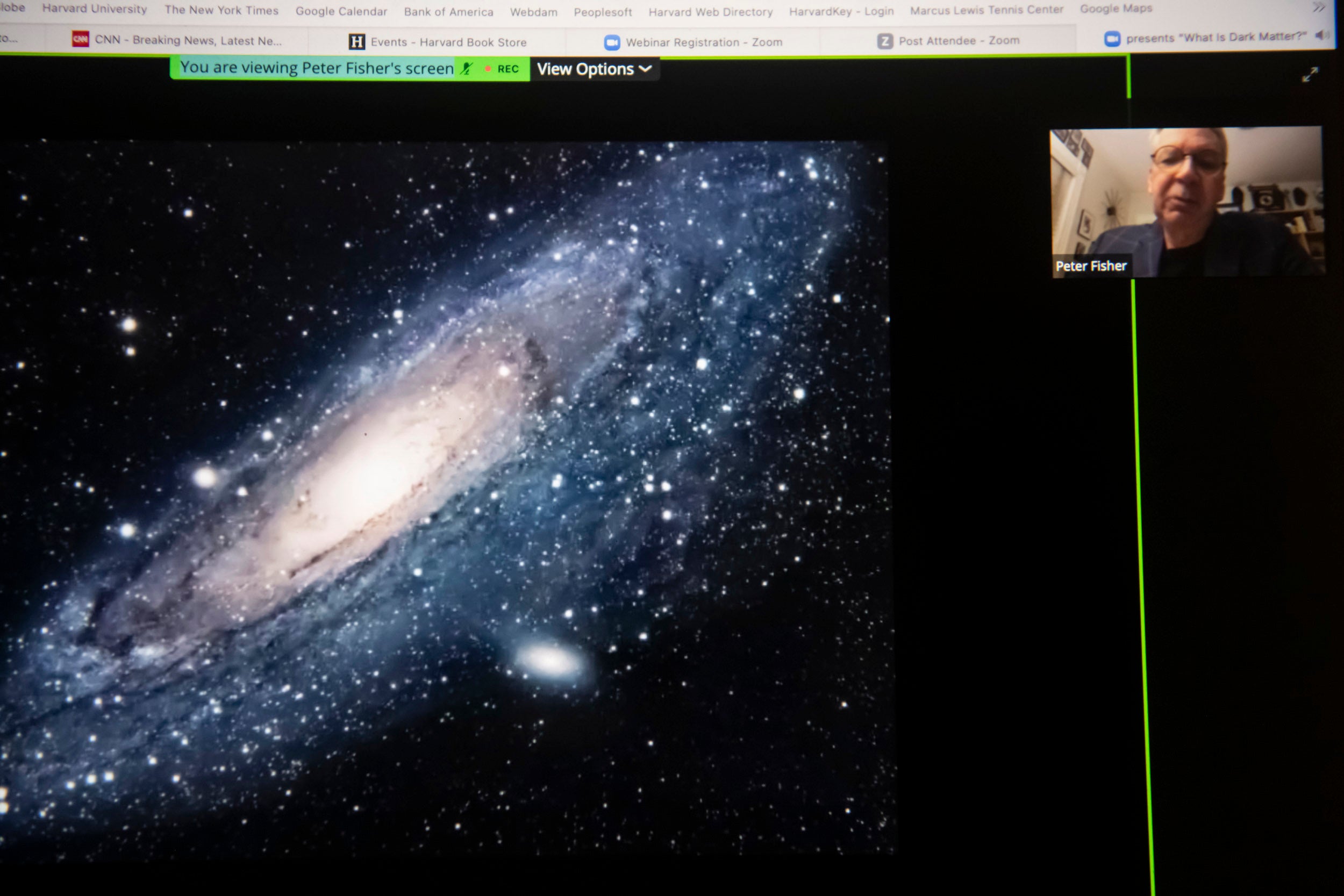

MIT physicist Peter Fisher showed a slide of the Andromeda galaxy, with its lush swirl of stars emanating out in a flat disc, containing roughly a trillion stars.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Mystery of dark matter — and search for WIMP

MIT physicist, author lays out clues to how we know they exist (even though we can’t see them), what they might be in Harvard book talk

Scientists know that dark matter exists because although we can’t see it, we can see the effects of what it does in the world, sort of like a ghost bumping around a haunted house. And we’re not sure what it is, but some think it may just be a WIMP.

Those are some of the insights that emerged from a Harvard Science Book Talk on Monday that featured an online conversation between Peter Fisher, the Thomas A. Frank Professor of Physics at MIT, who just wrote a book titled “What Is Dark Matter?,” and Melissa Franklin, Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics at Harvard.

Fisher opened the event, sponsored by the Harvard Division of Science, Harvard Library, and Harvard Book Store, with a short response to the question the title poses: “The answer is we don’t know.” He offered several possibilities, explaining that his subject could be a particle, a heavy particle, “tiny black holes from the beginning of the universe, or it could be something we haven’t even thought of.”

To shed some light on the topic, Fisher recounted the history of particle physics, from the invention of quantum mechanics in the 1930s to the development of the standard model theory in the 1990s, which explains three out of four known fundamental forces (electromagnetic, weak and strong interactions, but not gravity).

Parallel to the development of this science, astronomers studying the universe were making discoveries about the movement of the stars away from the Earth — proof the universe is expanding. That movement, astronomers realized, was happening faster than forces such as the gravity of the component stars could explain. “They studied the way galaxies moved with respect to each other, and the way stars moved within galaxies. And the only way they could come up with explaining how everything was moving in the biggest scales of the universe was the introduction of matter that we couldn’t see,” he said.

The answer, requiring all these disciplines, was that there “were actually two kinds of matter that we couldn’t see.” These were dark energy and dark matter. “Dark matter makes particles or stars within galaxies move more quickly than you’d expect from the mass in those galaxies,” he said.

To illustrate, Fisher shared a slide of the Andromeda galaxy, with its lush swirl of stars emanating out in a flat disc. “It looks very similar to the Milky Way in the middle,” he said, pointing out the “glowing region in the very middle of that: a big black hole about a million times the mass of our sun. There’s a lot of matter being pulled into the dense central region, and you can see there’s this beautiful pancake shape with spiral arms,” containing roughly a trillion stars.

“What’s particularly interesting is you can see that there’s a sharp end to the disc part. And that edge is really only explainable if you hypothesize that there is some substance called dark matter that is making a gravitational pull that makes that shape.”

Andromeda is not unique. In fact, Fisher explained, images of deep space provided by the Hubble Space Telescope reveal a striking consistency. “There have been very detailed measurements of literally thousands of galaxies, and they all share the same features,” he said. “A careful study of all these different kinds of galaxies always comes up with the same conclusion, which is the stars are moving too fast to be explainable by the amount of light coming from that galaxy,” he said. “This must denote the presence of dark matter around the galaxy.”

Franklin, paraphrasing Fisher’s book, likened the search to a ghost hunt. “If you have ghosts in your house moving things around, you can’t see them or hear them or feel them. So what you want to do is figure out from the movements what exactly is going on.”

What dark matter is, however, is much less clear. One theory is that it is a new kind of particle, a weakly interacting massive particle (or WIMP). If that theory is correct, said Fisher, dark matter is likely all around — but “here on Earth, it’s hard to find dark matter because there’s so much normal matter around. You have to look and think about galaxies as a whole” in order to get a large enough scale to study dark matter.

Another theory is that dark matter is primordial black holes, dating back to the origins of the universe. If that’s the case, Fisher noted, these “tiny” bits of matter “could just go straight through the Earth. They don’t pick up much matter. They can go straight through pretty much anything and nobody really notices it.”

The ongoing search, Fisher cautioned, will require continuing advancements in technology but also caution and a careful understanding of how our tools work. To illustrate what can go wrong, he described the nation’s Distant Early Warning Line, a system of radar stations along the Arctic Circle created as a defense against a possible Soviet missile attack during the Cold War. “These radar operators saw all kinds of stuff that it took years to explain,” he said, resulting in theories about UFOs that are still around. “Anytime you build a new device, you see things you don’t expect.”

As the search for dark matter continues, such meticulous discipline is vital. However, despite the many questions that remain, we can be confident that dark matter exists because “all of the measurements are made repeatedly using very different kinds of telescopes,” he said. The movement of stars, for example, has been observed with large optical telescopes and also radio telescopes. “It’s not a guarantee, but it gives one confidence that the same overall effect is observed in two very different ways.”