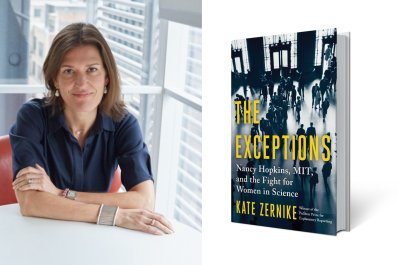

Women in academia and the sciences are finally getting their due: The key to mRNA vaccines—which helped bring COVID-19 vaccines to market so speedily—came from the lab of 65-year-old Katalin Karikó; Rochelle Walensky leads the Centers for Disease Control and this fall, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and six out of the eight Ivy League universities will be led by women presidents. While opportunities for women in academia and STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) careers have a long way to go, things are significantly better, and that is a result of an unparalled group effort by 16 female members of the MIT faculty to bring about change. Their work resulted in a groundbreaking admission by the school in 1999 of a pattern of marginalization of its female faculty. As a result of the report, the ranks of tenured women faculty at MIT grew significantly: universities across the country began fixing the gender gap in salaries—which many called "Nancy Hopkins raises" after the ringleader in the MIT group; the National Science Foundation's ADVANCE program spent $365 million over the next 25 years nationwide to establish programs to identify and address gender disparities and many other inequalities were addressed. The story of Nancy Hopkins and how she and her 15 colleagues fought for fair treatment is told in Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Kate Zernike's The Exceptions (Scribner, February). In the excerpt below from her book, Zernike shares the roots of how she came to research this triumph.

In March 1999, a story above the fold on the front page of the Boston Sunday Globe reported that the Massachusetts Institute of Technology had acknowledged long-standing discrimination against women on its science faculty. It was "an extraordinary admission," as an article on the front page of the New York Times called it two days later, by which point the news had traveled around the world by radio, television and a fever pitch of emails between female scientists who had long known they were not valued as highly as men but talked about it only among themselves, if at all. Here was one of the most prestigious institutions in the world, synonymous with scientific excellence. The discrimination had happened not in some dark age but in the 1990s, the dawn of a new millennium, decades after legislation and the women's movement had pushed open the doors of opportunity. Most women starting their careers at the time did not think bias would block them. Women who complained of discrimination typically ended up in the deadlock of he-said, she-said. Now the president of MIT was saying it was true.

That admission came about not because of a lawsuit or formal complaint, but because of the work of 16 women who had started as strangers, working in secret, and gathered their case so methodically—like the scientists they were—that MIT could not ignore them. They upset the usual assumptions about why there were so few women in science and math and unleashed a reckoning across the United States as other universities, philanthropies and government agencies rushed to address the bias and the disparities that had disadvantaged women for decades. "A climate change in the whole of academia," as an astronomer at the California Institute of Technology called it.

I was the reporter who wrote the story in the Globe. I had recognized that it might resonate—though I could not predict how much—because of my father, a physicist who had arrived in the United States in 1956 to work for a small engineering firm in Cambridge populated by MIT graduates and consultants. My parents had moved before I was born, but my father visited me often in Boston on his way to see his collaborators at Lincoln Laboratory, an MIT research center, and he had suggested that I look into the work that a physicist named Millie Dresselhaus at MIT—known as the "Queen of Carbon"—was doing to encourage more women to enter the profession.

I had ignored him, until I heard about the women at MIT. They made me think of my mother, who was around the same age as the oldest of them. My mother had wanted to go to law school when she graduated from college in 1954, but her father surveyed his lawyer friends in Toronto and told her that no one would hire her. So she went to business school instead, up the street from MIT, enrolling in the Harvard-Radcliffe Program in Business Administration, which was the only way women could attend the Harvard Business School. That year The Wall Street Journal reported on the program in the middle column of its front page, reserved for offbeat or "light" features. It quoted business leaders marveling that the Radcliffe girls were "just as smart as the boys," but lamenting that "too many marry too soon." ("They're too good-looking, they're just the right age, and there are too many men at the bank.") My mother herself worked in a bank after she finished, quit to get married, and raised three children, but always regretted that she had not gone to law school. Her decision to go when I was 7—I was the youngest of her three—became the defining event of my childhood. She inquired at Yale, where a man told her, "I wouldn't let my wife go to law school." She ended up instead at Pace University.

A year or two after she graduated, she was in the law library there and decided to look herself up in the Harvard Alumni Directory. There she found her name followed by a series of acronyms: BA, MBA, JD, W/M. Not recognizing the last one, she went to the key and discovered "wife and mother."

My mother was then commuting three hours a day to her job at a law firm in lower Manhattan and still made dinner most nights. I was about 12 and did not fully understand her fury as she came rushing out of the law library, where I was sitting on the steps. She drove home ranting, "W slash M! W slash M?" In time it became a family joke. But I can't say I had fathomed it even by the time I started my own career in Boston. Across the river, Cambridge was no longer the city where my parents had their first apartment; now it was tony restaurants and out-of-reach real estate prices. Twenty-five years after coeducation, I presumed my mother's experience was deep in the past.

The MIT women made me see it was not, at least not in science. They had identified the new shape of sex discrimination, more subtle but still pervasive. I was struck by their ingenuity, and how they had enlightened the men who ran the university. Their experience became a metric for how I thought about my own life and the questions and debates around women that I would write about. In time, what the MIT women had described began to look less faraway, more relevant. So much had changed, and yet.

Then as now, I saw the story as one of remarkable persistence and risk on the part of 16 women who did not consider themselves activists. Led by a reluctant feminist, they were more pragmatic than revolutionary. They were not interested in publicity; they just wanted to get on with their work. As I explored their story—and the story of women in science before and after them—the word that kept coming up, in different conjugations, was exception. Women who succeeded in science were called exceptional, as if it were unusual for them to be so bright. They were exceptional not because they could succeed at science but because of all they accomplished despite the hurdles. Many had pushed past discrimination for years by excusing individual situations or incidents as exceptional, explained not by bias but by circumstance. Only when they came together did the MIT women see the pattern. That recognition alone made them exceptional, too.

I had known Nancy Hopkins, the molecular biologist who came to lead them, for 20 years before I realized that she had started her life as Nancy Doe. Like John Doe or Jane Doe, the generic everywoman whose example tells the larger story. The exception who proved the rule.

▸ Adapted from The Exceptions, published by Scribner. Copyright © 2023 by Kate Zernike.