3 Questions: MIT goes interstellar with Voyager 2

MIT Kavli’s John Richardson describes MIT’s role in the historic passing of the Voyager 2 craft past the heliopause and into the interstellar medium.

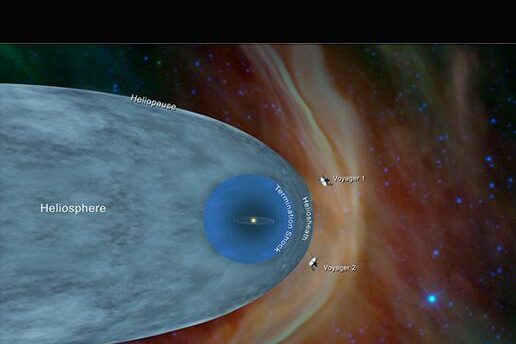

NASA announced today that the Voyager 2 spacecraft, some 11 billion miles from home, crossed the heliopause, the boundary between the bubble of space governed by charged particles from our sun and the interstellar medium, or material between stars, on Nov. 5. In an historic feat for the mission, Voyager 2’s plasma instrument, developed at MIT in the 1970s, is set to make the first direct measurements of the interstellar plasma.

The twin Voyager spacecraft were launched in 1977 on a mission to explore the solar system’s gas giant planets. With their initial missions achieved and expanded, the spacecraft have continued outward toward the edges of the solar system for the past four decades; today they are the most distant human-made objects from Earth. Voyager 1 is 13 billion miles from Earth and crossed into the interstellar medium in 2012, but its plasma instrument is no longer functioning.

Several researchers from MIT are working directly with data from the Voyager 2 plasma instrument. These include the instrument’s principal investigator, John Richardson, a principal research scientist in the MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, and John Belcher, the Class of 1992 Professor of Physics. Belcher was part of the original MIT team, led by Professor Herbert Bridge, that built the Voyager plasma instruments in the 1970s. Richardson answered some questions about the recent Voyager 2 discoveries.

Q. Why is Voyager 2 crossing the heliopause important?

A. Although Voyager 1 already crossed the heliopause in 2012, many questions about this boundary were left unanswered. The biggest was the role of the plasma that contains most of the mass of the charged particles in the solar system, which was not measured by Voyager 1. Our data have shown that there is a boundary layer 1.5 AU [139 million miles] in width inside the heliopause with enhanced densities and decreasing speeds coincident with an increase in the high energy galactic cosmic rays. We also found that the actual boundary, as defined by the plasma, occurs further in than previously thought based on energetic particle data.

Q. Was the heliopause location where you expected?

A: Before the Voyager spacecraft, the heliopause distance was uncertain by at least a factor of two. The Voyager 1 crossing at 122 AU [141 million miles] gave a position in one direction and at one time. The distance varies with time, and many models predict the heliosphere is not spherical. So we really didn’t know if Voyager 2 would cross three years ago or three years from now. The distance is very similar to that at Voyager 1, suggesting the heliosphere may be close to spherical.

Q. What will Voyager 2 see next?

A: Voyager 1 has shown us that the interstellar medium near the heliopause is greatly affected by solar storms. The surges in solar wind drive shocks into the interstellar medium, which then generate plasma waves. We hope to directly measure the plasma changes at these shocks. One controversy about the heliosphere is whether there is a bow shock in the interstellar medium upstream of the heliopause that heats, compresses, and slows the plasma. Our measurements of the plasma, particularly the temperature, could help resolve this question.