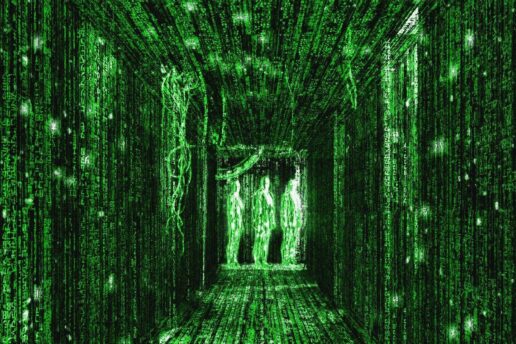

Are We Living in a Simulated World?

Probably not, but the idea is just crazy enough to be worth taking seriously.

The idea that the world we experience is an illusion being fed to us by powerful computers, popularized by the “Matrix” movies, is just crazy enough to be worth taking seriously. But if we’re going to be serious, it is important to distinguish between two very different questions. First: Could there be a richly experienced mental world that is not made of matter, as it appears to be, but of abstract data? And second: Is the world we actually experience—the universe as described by the laws of physics and the facts of cosmology—such a world?

The answer to the first question is pretty surely yes. In fact, humans occupy self-generated mind-worlds for an hour or two each day, when we dream during REM sleep. The objects we see in dreams are just patterns of electrical excitation in our brains. Analogously, virtual reality tunes us into data streams that we perceive as objects.

Dreams are transient, and at present virtual reality is not an all-encompassing experience. We humans still live the bulk of our lives in a shared reality, where we do things like eat, drink and get older. But many experts think that one day it will be possible to build artificial minds, wholly based on electronic circuitry, that will simulate human thought processes, including self-awareness. Such artificial minds, inhabiting programmed worlds, could well be oblivious to physical reality, despite being embedded within it.

To our second question—is our own perceived world manufactured, in fact, from such abstract data—the best answer is pretty surely no. First of all, the idea that the physical world we experience is a computer simulation begs a basic question: What is the computer made of?

Leaving that detail aside, there are many aspects of physics in our world that do not look like the product of an efficient world-simulator. For example, our most accurate formulation of the laws of physics depends on the idea that space and time are smooth and continuous. When you work with continuous numbers, instead of 0s and 1s, it becomes much more difficult, in a simulation, to maintain precision.

More generally, our world contains a lot of hidden complexity. We can calculate a proton’s properties based on fundamental laws, but those calculations are extremely complicated. It would be a poor strategy to build a simulated world out of such hard-to-compute ingredients.

The basic “Matrix” fantasy isn’t new. It is a computer-age variation on the philosophical notion of idealism, according to which so-called physical reality is at base mental, not material. According to the 18th-century philosopher Bishop Berkeley, the world reflects activity in the mind of God. But Samuel Johnson was not impressed with this theory, as a story told by his biographer James Boswell relates:

“We stood talking for some time together of Bishop Berkeley’s ingenious sophistry to prove the nonexistence of matter and that every thing in the universe is merely ideal.… I never shall forget the alacrity with which Johnson answered, striking his foot with mighty force against a large stone, till he rebounded from it—‘I refute it thus.’”

That kick is worth a thousand words. It is quite possible to imagine a simulated world. But if ours is such a world, then the mind that creates it, made of God knows what, works in very mysterious ways.

Originally appeared on January 9, 2020 on The Wall Street Journal website as ‘Are We Living in a Simulated World?‘

Frank Wilczek is the Herman Feshbach Professor of Physics at MIT, winner of the 2004 Nobel Prize in Physics, and author of the books Fundamentals: Ten Keys to Reality (2021), A Beautiful Question: Finding Nature’s Deep Design (2015), and The Lightness of Being: Mass, Ether, and the Unification of Forces (2009).