Exploring the nanoworld

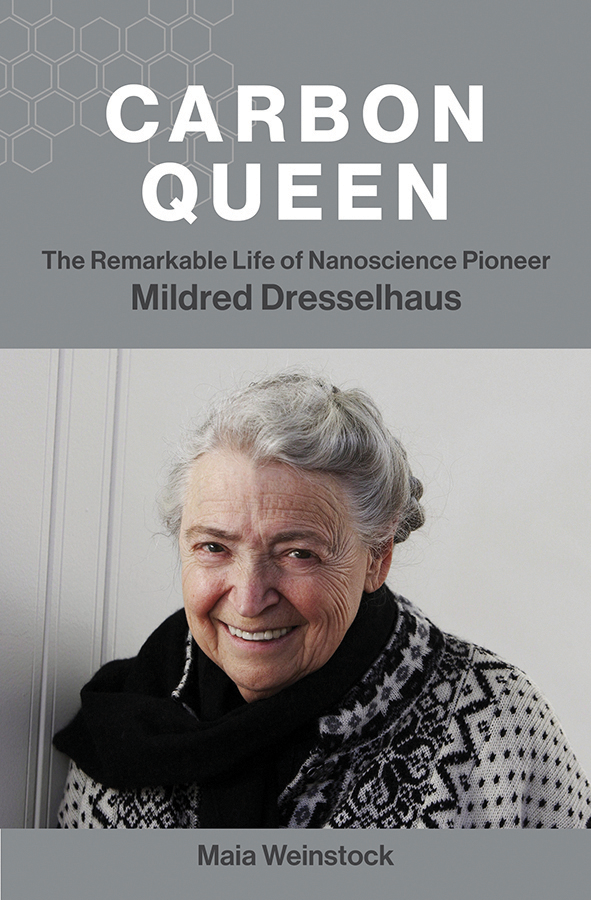

Maia Weinstock tells the life story of physicist Mildred Dresselhaus, who led research on carbon and nanomaterials at MIT for more than half a century.

When she was approached by the MIT Press with a list of people being considered for a biography, Maia Weinstock says, Mildred “Millie” Dresselhaus stood out from the rest.

“I felt I could really dig into her story, and I was very curious about what made her tick,” says Weinstock, a science writer and deputy editorial director in the MIT News Office. “I had heard legends of Millie and wanted to know more—why she had become so beloved in the MIT community and what her life was like as a pioneer in her field for so many decades.”

Weinstock’s curiosity resulted in Carbon Queen: The Remarkable Life of Nanoscience Pioneer Mildred Dresselhaus, coming out in March.

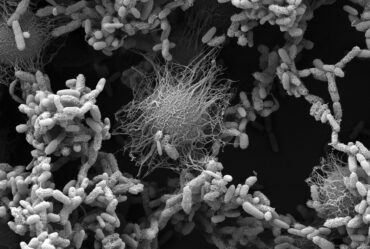

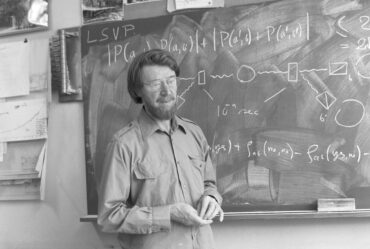

Dresselhaus, who died in 2017 at age 86, is best known for her groundbreaking work with nanomaterials. Over nearly 60 years at MIT, first at Lincoln Laboratory and then as a professor of electrical engineering and physics, she made influential discoveries about the electronic properties of carbon and other materials, contributing especially to the science of graphite, carbon nanotubes, and graphene.

Dresselhaus achieved many firsts in her storied career. The first female MIT Institute Professor and the first solo recipient of the international Kavli Prize, given biennially in the disciplines of astrophysics, nanoscience, and neuroscience, Dresselhaus helped pave the way for women and other underrepresented groups in the STEM fields. She overcame long odds to get there.

“One thing I had no idea about was her impoverished background. She came from a situation where, basically, her family had nothing,” Weinstock says. As the daughter of immigrants in 1930s New York City, Dresselhaus lived through one of the most difficult times in American history. To help keep her family afloat, she got her first job at just eight years old, as a tutor for a special-needs student. She also worked as a child laborer in a sweatshop, putting zippers together.

Weinstock was surprised as well to learn about Dresselhaus’s deep love of music.

“Music played a central role in every stage of her life,” she says. “Without music, she would not have become a scientist, or at least it would have been a very different path.” Dresselhaus displayed a flawless memory for music from the age of four and earned a scholarship to a music school alongside her brother, a violin prodigy. She would go on to make music a focal point in her family and in her professional life, continuing to play the violin at least two days a week until her death.

Weinstock hopes her book will inspire the next generation. “If I had a book like this when I was growing up,” she says, “it would have been really helpful to see this example and say, ‘I want to do something like that too.’”