For all humankind

Political science and physics major Leela Fredlund wants to ensure fairness and justice prevail in humanity’s leap into space.

Can a government promote morality? How much trust should people place in their government?

Such fundamental questions of political philosophy and ethics intrigue Leela Fredlund, a senior majoring in political science and physics. She has parsed these topics in ancient Greek texts, interrogated them in formal classroom recitations, and debated them informally with student friends. But for Fredlund, there is perhaps no better venue for exploring these classic problems than space.

“I realized that I could raise very interesting questions at the intersection of astronomy and political science,” says Fredlund. Through undergraduate projects at MIT and at institutions such as NASA, Fredlund has been focused on the ways governments are shaping humanity’s expanding ventures off planet.

“Do we believe governments have our best interests at heart?” she asks. “Space feels like a very obvious frontier to test that question.”

Ethics rules

When Fredlund arrived at MIT from her surfside California hometown, she had already decided to double major in science (chemistry, at that time) and philosophy. “In high school, I was very interested in thinking through my own political beliefs,” she recalls. “I was really worried that at a STEM school like MIT I wouldn’t have a forum for the kinds of discussions I found important.”

In Concourse, a first-year learning community, she found a base. “Concourse requires a course called Becoming Human: Ancient Greek Perspectives on the Good Life (CC.110), where we study ancient Greek political philosophy through introductory ethics texts by Aristotle and Plato,” she says. “We had incredible debates about applying the concepts we were learning to our daily lives and to modern political issues; my moral code shifted as a result of the class and I really felt like I was just benefiting as a person from it.”

Becoming Human proved pivotal to Fredlund’s academic evolution. She signed up as a teaching assistant for the class, a gig that she maintained through her senior year, and found a close mentor in its instructor, Senior Lecturer Linda R. Rabieh. By her first-year spring, Fredlund knew she would major in political science. “I really liked the idea of this smaller department that would be like Concourse,” she says. “I believed that political science would offer a community that cared a lot about ethical questions and would be a space where I could have my beliefs challenged, think about issues that I hadn’t thought a lot about before, potentially change my mind on some of the big questions, and generally expand my horizons.”

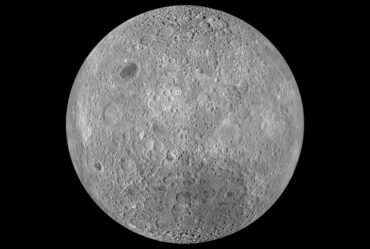

Firmly rooted in political science, Fredlund sought a path to marry it somehow with her other major, now physics. The answer emerged for her in sophomore year, in class 17.801 (Political Science Scope and Methods). “I remembered when I was much younger I thought I would grow up and become an astronaut, and became very interested in astronomy and space travel,” she says. “It was easy to get back into those subjects, and so I began to dig into questions related to space policy, space tourism, and exploitation of resources on other planets.”

Fredlund’s year-long project for 17.801, a 600-participant survey experiment, probed public perspectives on space development, especially attitudes toward government versus private initiatives. Her study yielded a number of novel findings: Respondents overwhelmingly supported a major expansion of ambitious, government-backed space missions, such as Mars exploration, to “push the frontiers of human capability,” says Fredlund. “It felt like a space race sentiment.” Her survey also revealed a preference for NASA collaborations with friendly nations like the U.K., rather than private companies.

“We hold governments to a different moral standard than individuals, so a private-sector space company directing exploration or resource extraction space missions might put its commercial ambitions and goals first,” she says.

Making Mars accessible

Fredlund found the ethical problems entailed in space development endlessly fascinating. To solidify her technical understanding of the subject, she took as many astronomy and astrophysics classes as her schedule would allow. She also landed a series of internships relevant to her interests.

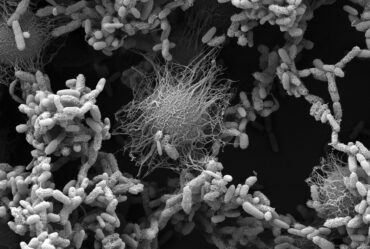

Over summer 2022, she worked at NASA researching the kind and location of facilities needed to receive Mars samples after the mission’s planned return to Earth in the 2030s. Fredlund found herself confronting the kinds of big questions she most likes.

“I was working with the European Space Agency to see who legally owns the samples we get back from Mars, which is a super interesting question because there is no precedent,” she says. “The Outer Space Treaty, which was made in the ’60s, had not planned for an international collaboration that would bring treasures back from another planet.”

Last summer and during senior year, Fredlund interned for the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, researching issues of accessibility in the space sector, seeking out promising new technologies that might permit physically and mentally disabled persons to participate in the space sector. “I met scientists who are trying to make the International Space Station accessible to people with auditory and visual deficits,” she says. This goal resonates for Fredlund, who has been highly engaged in the MIT Panhellenic Council to make campus Greek life more inclusive to diverse communities.

International space law

Fredlund’s post-MIT plans are rapidly falling into place. “I spent a lot of time talking to NASA’s legal and international relations teams, who are like diplomats to the European Space Agency,” she says. “They are savvy about working with other countries in space development.” Through this exposure, “I became very interested in the international law side of space questions,” says Fredlund. “I would like to help ensure we continue to operate in good faith, and that people prioritize the science in international collaborations.”

In the next two years, Fredlund aims to cement her technical background by earning a master’s degree in astronomy or astrophysics. Then she heads to Harvard Law School. After that, she imagines herself at the United Nations or NASA, interpreting international law, trying to ensure that the space sector remains a place for fair and truly cooperative ventures.

“The space sector is developing so quickly, I’m not entirely sure what the big questions will be six years from now,” says Fredlund. “There is a lot of uncertainty and I think uncertainty is exciting.”