Gravitational-wave detectors start next observing run to explore the secrets of the universe

The next run will be the most sensitive search yet for gravitational waves.

The following article is adapted from a press release issued by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) Laboratory, in collaboration with the LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration. LIGO is funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and operated by Caltech and MIT, which conceived and built the project.

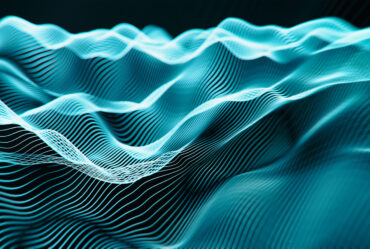

On Wednesday, the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA (LVK) collaboration began a new observing run with upgraded instruments, new and even more accurate signal models, and more advanced data analysis methods. The LVK collaboration consists of scientists across the globe who use a network of observatories — LIGO in the United States, Virgo in Europe, and KAGRA in Japan — to search for gravitational waves, or ripples in space-time, generated by colliding black holes and other extreme cosmic events.

This observing run, known as O4, promises to take gravitational-wave astronomy to the next level. Beginning on May 24 and lasting 20 months, including up to two months of commissioning breaks, O4 will be the most sensitive search yet for gravitational waves. LIGO will resume operations May 24, while Virgo will join later in the year. KAGRA will join for one month, beginning May 24, rejoining later in the run after some upgrades.

“Thanks to the work of more than a thousand people around the world over the last few years, we’ll get our deepest glimpse of the gravitational-wave universe yet,” says Jess McIver, the deputy spokesperson for the LIGO Scientific Collaboration (LSC). “A greater reach means we will learn more about black holes and neutron stars and increases the chances we find something new. We’re very excited to see what’s out there.”

The Virgo detector will continue commissioning activities in order to increase its sensitivity before joining O4 later this year. “Over the past few months we have identified various noise sources and have made good progress in sensitivity, but it is not yet at its design goal,” says recently elected Virgo spokesperson Gianluca Gemme. “We are convinced that achieving the best detector sensitivity is the best way to maximize its discovery potential.”

KAGRA is now running with the sensitivity planned for the beginning of O4. Jun’ichi Yokoyama, the chair of KAGRA Scientific Congress, says, “KAGRA is the first 2.5th generation detector in the world which started 20 years after LIGO. We will join O4 for one month and resume commissioning to further improve the sensitivity toward our first detection.”

With the detectors’ increased sensitivity, O4 will observe a larger fraction of the universe than previous observing runs.

This increased sensitivity will result in a higher rate of observed gravitational-wave signals and in the ability to extract more physical information from the data. This increased signal fidelity will improve scientists’ ability to test Einstein’s theory of general relativity and infer the true population of dead stars in the local universe.

“Data from the previous runs have answered some questions but also created new puzzles. We have discovered that the masses of black holes in our binaries seem to include a cluster at roughly 35 solar masses, but we don’t quite yet know what astrophysical processes are creating that feature, nor whether there are other ‘bumps’ in the mass distribution. More sources will help,” says Salvatore Vitale, an associate professor at MIT, describing the importance of increasing the sensitivity of the gravitational-wave detectors.

The first gravitational-wave signals were detected in 2015. Two years later, LIGO and Virgo detected a merger of two neutron stars, which caused an explosion called a kilonova, subsequently observed by dozens of telescopes around the world. So far, the global network has detected more than 80 black hole mergers, two probable neutron star mergers, and a few events that were most likely black holes merging with neutron stars. During O4, researchers expect to observe even more energetic cosmic events and gain new insights into the nature of the universe.

As in previous observing runs, alerts about gravitational-wave detection candidates will be distributed publicly during O4.

LIGO is funded by the NSF, and operated by Caltech and MIT, which conceived and built the project. Financial support for the Advanced LIGO project was led by NSF with Germany (Max Planck Society), the U.K. (Science and Technology Facilities Council) and Australia (Australian Research Council) making significant commitments and contributions to the project. More than 1,500 scientists from around the world participate in the effort through the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, which includes the GEO Collaboration.

The Virgo Collaboration is currently composed of approximately 850 members from 143 institutions in 15 different (mainly European) countries. The European Gravitational Observatory (EGO) hosts the Virgo detector near Pisa in Italy, and is funded by Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) in France, the Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN) in Italy, and the National Institute for Subatomic Physics (Nikhef) in the Netherlands.

KAGRA is the laser interferometer with 3-kilometer-arm-length in Kamioka, Gifu, Japan. The host institute is the Institute for Cosmic Ray Research (ICRR), the University of Tokyo, and the project is co-hosted by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) and High Energy Accelerator Research Organization (KEK). The KAGRA collaboration is composed of over 480 members from 115 institutes in 17 countries/regions. Resources for researchers are accessible from http://gwwiki.icrr.u-tokyo.ac.jp/JGWwiki/KAGRA.