“Hanging it over the edge”: Remembering astronaut and physicist Ronald McNair PhD ’76

Courtesy of MIT | YouTube

“If anything is worth doing, if anything is worth living, you’ve got to take a chance,” said Charles Bolden, a colonel in the US Marine Corps, when describing his fellow astronaut Ronald E. McNair’s approach to life.

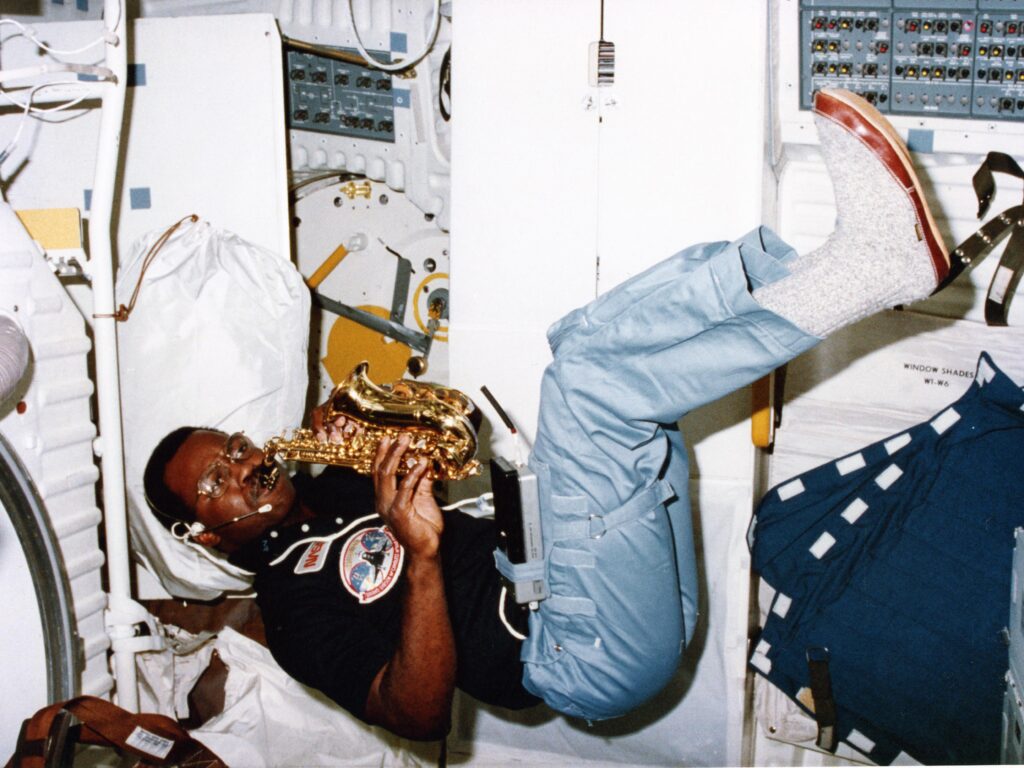

McNair earned his PhD in Physics from MIT in 1976, and went on to join the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). He became the second African American in space during the 1984 launch of the Space Shuttle Challenger, where he served as a mission specialist.

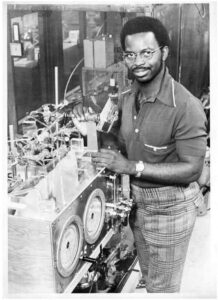

From an early age McNair proved adept with technology, for which he was affectionately known as “Gizmo.” He was raised in South Carolina by his father Carl, an automobile body repairman, and his mother Pearl, a high school teacher. As a young person he made his own contribution to the family finances by working in the local cotton fields. His family’s hard work, the Soviet launch of Sputnik, a community of faith, and a love of music provided some of the connective tissue of his early years.

The explosion of Challenger in January 1986 shocked millions of viewers all over the world. The mission had been designed to include unprecedented racial, ethnic, and gender diversity, and was carrying the first private citizen, high school teacher Christa McAuliffe, into space. A launch that began with great promise ended a little over a minute later, taking the lives of all seven aboard. Faulty O-rings likely caused a fuel leakage that led to the conflagration. This month marks the 35th anniversary of that terrible day.

Valedictorian of his high school class, McNair earned his Bachelor’s in physics from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University (NC A&T). He began the study of karate as an undergraduate, which according to friends appealed to him as a means to strengthen his self-discipline and his capacity for grace under pressure.

He became a Ford Foundation fellow, and though the thought of attending MIT was intimidating, he overcame his trepidation. “He believed that if your life experience was not a full one, then there was no point in leaving home,” said contemporary Shirley Jackson ’68, PhD ’73.

Jackson remembered that during his tenure at MIT, “[McNair] laughed a lot… the laughter was his personal celebration that signified his excitement about the experience, about extending himself, about taking himself to another plane.” Friends and colleagues often heard him refer to this as “hanging it over the edge,” a joyous engagement in the risks of living fully and pushing oneself as far as possible.

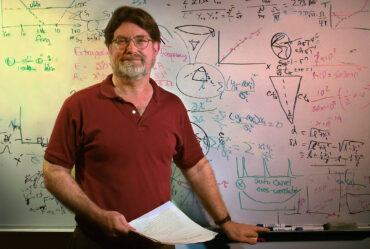

Bolden recounted, “Ron loved to walk up to the edge and see just how far you could get over there.” In the words of McNair’s thesis supervisor and director of the spectroscopy lab Prof. Michael S. Feld, “He learned to set bold goals for himself… and then to focus all his talent, his strength, and his concentration towards achievement of these goals.”

His determination was tested beyond the usual trials of graduate study when McNair’s bag was stolen, containing two years of specialized and collaborative data that provided the underpinning for his doctoral thesis. However, Feld said McNair never complained. He started again, and produced a second set of data that was better than the first in less than a year, maintaining his original completion schedule. According to Feld, “This was typical of the way he worked to accomplish his goals.”

According to Institute archives, for his graduate study McNair performed some of the earliest development of chemical HF/DF and high-pressure CO lasers. His later experiments and theoretical analysis of the interaction of intense CO2 laser radiation with molecular gases provided new understandings and applications for highly excited polyatomic molecules.

McNair completed his PhD in 1976, the same year he won the AAU Karate Gold Medal. A published expert in his area, McNair accepted a position with Hughes Research Laboratories in California. While there, he applied and was among the first non-test pilots to be accepted for training as NASA shuttle personnel.

Upon completion of his training, McNair worked at the Shuttle Avionics Integration Laboratory for four years before joining the crew of the Space Shuttle Challenger. During that 1984 mission, Challenger orbited the earth 122 times and launched a $75 million communications satellite, for which McNair operated Challenger’s remote manipulator arms.

“Truly there is no more beautiful sight than to see the earth from space beyond,” McNair reflected on this experience. “This planet is an exquisite oasis. Warmth emanates from the earth when you look at her from space… My wish is that we would allow this planet to be the beautiful oasis that she is, and allow ourselves to live more in the peace that she generates.”

According to Jackson, McNair himself embraced that sentiment and found beauty in the smallest and largest of things. For McNair, “the sacredness of the world also manifested itself in the endowment of some… seemingly ordinary creature, like a bird.”

Following the Challenger tragedy, the MIT Corporation dedicated and renamed the building which housed the Center for Space Research (CSR) in McNair’s honor so that, in the words of MIT President Paul Gray, “in years to come, MIT students, members of the MIT family… will have before them a tangible reminder of a life worthy of emulation.” Following a major grant from the Kavli Foundation in 2004, the CSR became the MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research (MKI), and continues to be housed in the McNair Building. Additionally, the Black Alumni/ae of MIT (BAMIT) established a scholarship in his name for black undergraduates.

“It was the fullness of him that made him remarkable,” said President Gray at the McNair Building’s dedication, “that gave him the many ways of seeing and understanding and engaging in the world.” He notably praised McNair for the way the physicist honored diverse cultures and interests, calling him a “builder of bridges between people” and saying that it is “the celebration of pluralism, that we as an institution and as a society… should strive for.”

McNair was known for his teaching and mentorship of others, and giving back to the community. Carol Morris, President of the Black Students Union in 1986, shared what she had learned from McNair: “His message to us was [that] failure only means not trying, and that if we were doing our best and reaching beyond our limits, then we were winners regardless of the outcome of our endeavors – or as he more eloquently put it, ‘you all here at MIT are hanging it over the edge. You are all winners.’”