How chess plays out at MIT

For decades, experts at the Institute have been shaping the future of the game.

Chess has a long history at MIT that began decades before 62 million households tuned in to Netflix’s miniseries “The Queen’s Gambit.” Though the show ranked as Netflix’s No. 1 in 63 countries within its first month, and sparked a global surge in the sale of chess sets and books, several members of MIT’s chess club say, with a laugh, that they haven’t seen it yet.

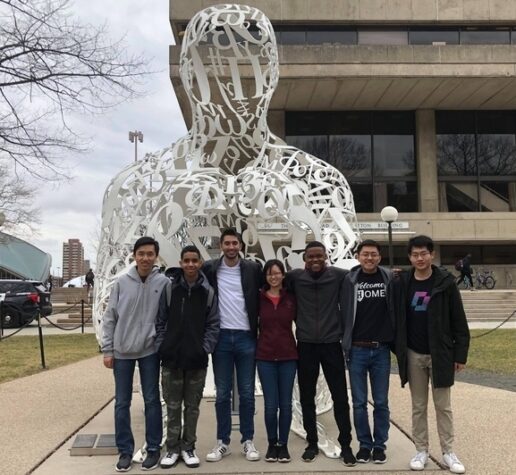

Tyrone Davis III, a junior computer science major, a U.S. National Chess Master, and the president of MIT’s chess club, says he plans to watch the miniseries eventually. For now, he says it’s been exciting to see growing public interest around the game he’s been playing since middle school.

“The hardest thing about chess is the beginning stages,” Davis says. “Once you learn how the pieces move, then you can have fun. But that’s only after you go through the difficult beginning time of learning how everything works. I hope the show could help motivate people through those tough beginning stages, so they can actually start having fun.”

A history of chess at MIT

“The Queen’s Gambit” was released on Netflix last October, and is based on a novel of the same name written in 1983 by Walter Tevis. The novel and television show follow a rising chess star named Beth during the 1950s and ’60s, as she ascends from child prodigy to international success.

During the same time period (in real life), artificial intelligence experts at MIT were shaping the future of chess.

Throughout the early 1900s, scientists and chess players around the world dreamed of a chess-playing machine. In 1951, English computer scientist Dietrich Prinz successfully created one, but it was not powerful enough to play a complete game. Then, in 1958, an IBM programmer developed a much stronger chess-playing machine, but novice players could still easily beat it.

The first computer to play chess “convincingly” was the Kotok-McCarthy computer program, developed by MIT students between 1959 and 1962. The students worked with John McCarthy, a computer scientist and cognitive scientist at MIT. In 1966, the Kotok-McCarthy program participated in and lost the first-ever chess match between two machines.

The first chess program to ever be ranked and to win against a human during a tournament was also developed at MIT. The Mac Hack, as the program came to be called, was written by computer programmer Richard Greenblatt. As a student at MIT and an avid chess player, Greenblatt published his work in a 1967 paper entitled “The Greenblatt Chess Program.”

Hubert Dreyfus, a prominent MIT professor of philosophy at the time, had previously noted the shortcomings of chess-playing machines. Then, he lost to the Greenblatt machine.

Meet MIT’s chess team

In 1996, Deep Blue, an IBM machine, became the first computer to beat a world champion in chess. Now, artificial intelligence can play better than most humans.

Online chess platforms are now extremely popular, enabling players to connect across the globe and also practice against artificial intelligence — which has been very handy amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

Several hundred members of the MIT community subscribe to the MIT Chess Club’s email list. Between 15 and 20 of those people consistently show up for weekly Friday afternoon club meetings, which now occur online and allow players to practice against one another.

“There’s a sort of latent energy at MIT of a lot of people that are vaguely interested in chess,” says William Cuozzo, a junior majoring in physics and computer science, and a member of MIT’s chess team executive board. “A lot of people are somewhat interested in chess, but they just don’t play that often, or they never got over that initial hump of learning how to play.”

Aileen Ma, a junior in computer science and a member of MIT’s chess team executive board, says she hopes that the show will inspire people to take up chess as a new hobby.

“Even though I haven’t seen the show, I had a lot of my friends who have and they’ve said ‘I had no idea chess was so exciting,’ she says of “The Queen’s Gambit.” “And it’s really great to see female representation, because there’s a lot of female grandmasters out there.”

Before the pandemic brought a halt to on-campus activities, MIT’s chess club hosted one U.S. Chess Federation tournament every academic year. They also previously attended the Pan-American Collegiate, Ivy League Challenge, and World Amateur Team tournaments, and played with many universities in the Boston area.

The club has turned to websites like lichess.org to keep playing chess remotely, often with brand-new opponents.

In “The Queen’s Gambit,” Beth faces many of her most formidable opponents in Moscow, Russia (then the USSR). In mid-October this semester, MIT’s chess team faced off against players from the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (MIPT) for a weekend-long lichess.org tournament. After 171 games played, and almost 12,000 total moves, MIPT earned a narrow victory.

“I think one of the best parts of these online matches is that everyone has a chance to participate and earn points for the team,” says Ma. “It was a lot of fun. A lot of people who don’t normally come to meetings came to help us try to improve our score.”

Learning the game

Davis grew up in the Bronx, where he practiced chess in Union Square and other parks around New York City. Being able to sit down and look at a board for six hours at a time at a young age, Davis says, improved his ability to concentrate.

“Depending on when in your life you find the game, it could definitely impact you in different ways,” Davis says. “It definitely helped me be able to sit down for hours and apply my brain to certain long tasks that require a lot of attention span.”

Cuozzo learned to play chess at a very young age, but says he really got interested in playing during high school, when a friend challenged and subsequently “crushed” him. “I wanted to at least be able to play with him,” he says.

“The Queen’s Gambit” has spurred public interest in learning the game of chess. And the flood of excitement comes at a good time — there are now more resources to learn chess than ever before, says Howard Zhong, a sophomore majoring in computer science and math, and a U.S. National Master. Zhong learned to play chess at age 6, and is currently a member of MIT’s chess team. “Even five to 10 years ago, there were not as many resources online,” Zhong says. “The majority was just reading books, or having a coach. But now, with so many online resources, I think it’s really made it a lot easier to improve.”

Zhong and Cuozzo recommend watching chess tutorials like ChessNetwork on YouTube, and exploring practice resources on websites like chess.com or lichess.org. Davis says it’s important not to be discouraged by the initial learning curve — it may take a few days or weeks to learn the moves.

MIT’s chess club welcomes people of all levels of skill. Members of the MIT community who are interested in participating can sign up for the mailing list. The club plans to participate in more virtual tournaments and games in the coming months.

“Sometimes the public perception of chess is that if you’re not really good, it’s not worth playing,” Ma says. “But recently, I think there’s just been a lot more effort toward trying to get people involved even at the more intermediate levels of chess.”