Room temperature electrical control could heat up future technology development

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — An old physical phenomenon, known as the Hall effect, has revealed some new tricks, according to a team co-led by researchers at Penn State and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). They reported their findings, which they said have potential implications for understanding fundamental physics of quantum materials and developing applied technologies such as quantum communication and harvesting energy via radio frequencies, this week (Oct. 21) in Nature Materials.

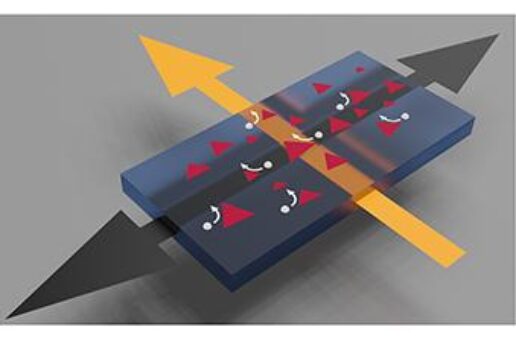

The conventional Hall effect occurs only in electrical conductors or semiconductors in the presence of a magnetic field. It is characterized by a newly formed voltage, called the Hall voltage, that can be measured perpendicularly to the current and is directly proportional to the applied current.

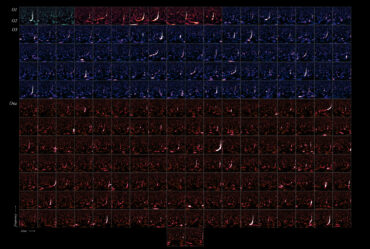

However, the newly discovered nonreciprocal Hall effect does not require a magnetic field. Discovered by teams led by Zhiqiang Mao, professor of physics, of materials science and engineering and of chemistry at Penn State, and Liang Fu, professor of physics at MIT, this effect is instead denoted by a relationship between the Hall voltage and the applied current that can be described mathematically: The Hall voltage is always proportional to the square of the current. They made the finding in microstructures comprising textured platinum nanoparticles deposited on silicon.

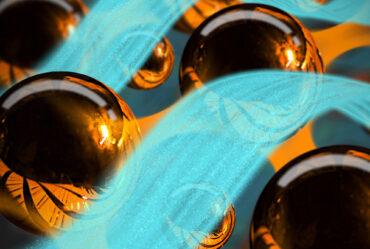

Unlike the conventional Hall effect, which is driven by a force induced by the magnetic field, the nonreciprocal Hall effect arises from flowing conduction electrons — which are particles that carry the electrical charge — interacting with the textured platinum nanoparticles.

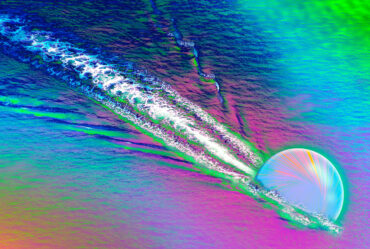

“In this work, we report the first observation of a room-temperature colossal nonreciprocal Hall effect,” Mao said, explaining that pronounced geometric asymmetric scatterings of the textured platinum nanoparticles enabled the observation. “We also showcased the potential application of this effect for broadband frequency mixing and wireless microwave detection. This underscores the vast potential of utilizing nonreciprocal Hall devices for terahertz communication, imaging and energy harvesting.”

The work hinges on understanding how electrons can scatter asymmetrically when interacting with nonsymmetrical particles in a material. This process results in a violation of Ohm’s law, a fundamental tenet described by physicist Georg Ohm in the 1827, that states that the current through a conductor is proportional to the applied voltage. Under this law, the Hall voltage should be zero in the absence of a magnetic field. However, Mao said, a nonreciprocal Hall voltage that scales quadratically with current in textured platinum nanoparticles at zero magnetic field challenges this principle.

According to Mao, the finding is even more interesting because, typically, investigations of these behaviors require low temperatures of less than minus 280 degrees Fahrenheit. However, in this study, the asymmetric structure of the deposited platinum nanoparticles appears to generate the nonreciprocal Hall effect even at room temperature. The work could have potential applications in technologies like quantum rectification, or converting alternating currents to direct current, and photodetection, which involves making electrical signals from light, Mao said.

“This breakthrough deepens our understanding of charge transport in materials,” Mao said, emphasizing that the key to the presence of the nonreciprocal Hall effect in textured platinum nanoparticles is asymmetric electron scattering. “This asymmetry reveals uneven features in what would otherwise be a uniform landscape, and it is in these areas that we are most likely to uncover new insights.”

Co-authors affiliated with Penn State include Lujin Min, who was a doctoral student in materials science and engineering at the time of the research and is now a postdoctoral associate at Cornell University; Seng Huat Lee, assistant research professor in the Materials Research Institute (MRI); Yu Wang, research technician with MRI’s 2D Crystal Consortium; Sai Venkata Gayathri Ayyagari, graduate student in materials science and engineering; Leixin Miao, who was a doctoral student at the time of the research and is now a yield development engineer at Intel; and Nasim Alem, associate professor of materials science and engineering. Yang Zhang, Yugo Onishi and Liang Fu, Department of Physics, MIT; and Zhijian Xie, North Carolina Agriculture & Technical State University, also collaborated on the study.

Penn State, the U.S. National Science Foundation, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory and the U.S. Army Research Office through the Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the Funai Overseas Scholarship helped support this research.