Astronomers nail down the origins of rare loner dwarf galaxies

The results provide a blueprint for finding such systems in the universe’s quieter, emptier regions.

By definition, dwarf galaxies are small and dim, with just a fraction of the stars found in the Milky Way and other galaxies. There are, however, giants among the dwarfs: Ultra-diffuse galaxies, or UDGs, are dwarf systems that contain relatively few stars but are scattered over vast regions. Because they are so diffuse, these systems are difficult to detect, though most have been found tucked within clusters of larger, brighter galaxies.

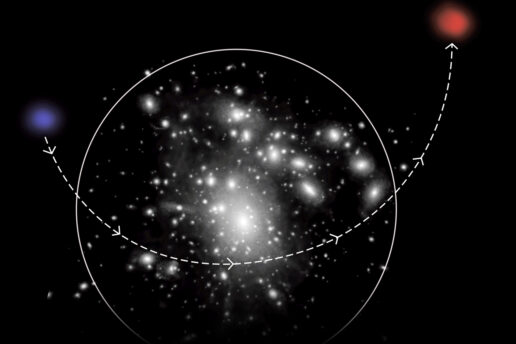

Now astronomers from MIT, the University of California at Riverside, and elsewhere have used detailed simulations to detect “quenched” UDGs — a rare type of dwarf galaxy that has stopped generating stars. They identified several such systems in their simulations and found the galaxies were not in clusters, but rather exiled in voids — quiet, nearly empty regions of the universe.

This isolation goes against astronomers’ predictions of how quenched UDGs should form. So, the team used the same simulations to rewind the dwarf systems’ evolution and see exactly how they came to be.

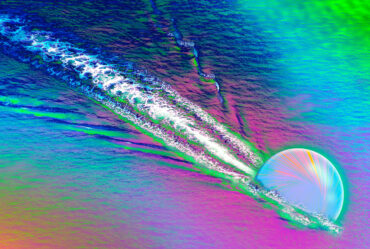

The researchers found that quenched UDGs likely coalesced within halos of dark matter with unusually high angular momentum. Like a cotton candy machine, this extreme environment may have spun out dwarf galaxies that were anomalously stretched out.

These UDGs then evolved within galaxy clusters, like most UDGs. But interactions within the cluster likely ejected the dwarfs into the void, giving them wide, boomerang-like trajectories known as “backsplash” orbits. In the process, the galaxies’ gas was stripped away, leaving the galaxies “quenched” and unable to produce new stars.

The simulations showed that such UDGs should be more common than what has been observed. The researchers say their results, published today in Nature Astronomy, provide a blueprint for astronomers to go looking for these dwarfish giants in the universe’s voids.

“We always strive to get a complete consensus of the galaxies that we have in the universe,” says Mark Vogelsberger, associate professor of physics at MIT. “This study is adding a new population of galaxies that the simulation actually predicts. And we now have to look for them in the real universe.”

Vogelsberger co-led the study with Laura Sales of UC Riverside and José A. Benavides of the Institute of Theoretical and Experimental Astronomy in Argentina.

Red v blue

The team’s search for quenched UDGs began with a simple survey for UDG satellites — ultra-diffuse systems that reside outside galaxy clusters. Astronomers predict that UDGs within clusters should be quenched, as they would be surrounded by other galaxies that would essentially rub out the UDG’s already-diffuse gas and shut off star production. Quenched UDGs in clusters should then consist mainly of old stars and appear red in color.

If UDGs exist outside clusters, in the void, they are expected to continue churning out stars, as there would be no competing gas from other galaxies to quench them. UDGs in the void, therefore, are predicted to be rich with new stars, and to appear blue.

When the team surveyed previous detections of UDG satellites, outside clusters, they found most were blue as expected — but a few were red.

“That’s what caught our attention,” Sales says. “And we thought, ‘What are they doing there? How did they form?’ There was no good explanation.”

Galactic cube

To find one, the researchers looked to TNG50, a detailed cosmological simulation of galaxy formation developed by Vogelsberger and others at MIT and elsewhere. The simulation runs on some of the most powerful supercomputers in the world and is designed to evolve a large volume of the universe, from conditions resembling those shortly after the Big Bang to the present day.

The simulation is based on fundamental principles of physics and the complex interactions between matter and gas, and its results have been shown in many scenarios to agree with what astronomers have observed in the actual universe. TNG50 has therefore been used as an accurate model for how and where many types of galaxies evolve through time.

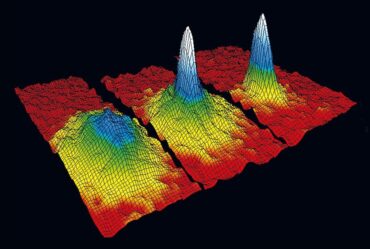

In their new study, Vogelsberger, Sales, and Benavides used TNG50 to first see if they could spot quenched UDGs outside galaxy clusters. They started with a cube of the early universe measuring about 150 million light years wide, and ran the simulation forward, up through the present day. Then they searched the simulation specifically for UDGs in voids, and found most of the ones they detected were blue, as expected. But a surprising number — about 25 percent — were red, or quenched.

They zeroed in on these red satellite dwarfs and used the same simulation, this time as a sort of time machine to see how, when, and where these galaxies originated. They found that the systems were initially part of clusters but were somehow thrown out into the void, on a more elliptical, “backsplash” orbit.

“These orbits are almost like those of comets in our solar system,” Sales says. “Some go out and orbit back around, and others may come in once and then never again. For quenched UDGs, because their orbits are so elliptical, they haven’t had time to come back, even over the entire age of the universe. They are still out there in the field.”

The simulations also showed that the quenched UDGs’ red color arose from their ejection — a violent process that stripped away the galaxies’ star-forming gas, leaving it quenched and red. Running the simulations further back in time, the team observed that the tiny systems, like all galaxies, originated in halos of dark matter, where gas coalesces into galactic disks. But for quenched UDGs, the halos appeared to spin faster than normal, generating stretched out, ultra-diffuse galaxies.

Now that the researchers have a better understanding of where and how quenched UDGs arose, they hope astronomers can use their results to tune telescopes, to identify more such isolated red dwarfs — which the simulations suggest must be lurking in larger numbers than what astronomers have so far detected.

“It’s quite surprising that the simulations can really produce all these very small objects,” Vogelsberger says. “We predict there should be more of this kind of galaxy out there. This makes our work quite exciting.”