NASA selects three MIT alumni for astronaut training

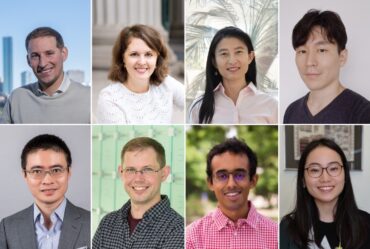

Marcos Berríos ’06, Christina Birch PhD ’15, and Christopher Williams PhD ’12 make up a third of the 2021 NASA astronaut candidate class.

On Monday, MIT confirmed once again its status as a popular launchpad for future astronauts. NASA announced that three MIT alumni are among its 10-member astronaut candidate class of 2021.

Marcos Berríos ’06, who graduated from the Department of Mechanical Engineering; Christina Birch PhD ’15, who earned a doctorate from the Department of Biological Engineering, and Christopher Williams PhD ’12, who earned a doctorate from the Department of Physics, were introduced as members of the newest astronaut class, NASA’s first in four years, during an event near NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston.

They are among 10 new U.S. astronaut candidates chosen from over 12,000 applicants. The three aim to boost the total number of MIT astronaut alumni to 44, of the 360 NASA selected by NASA to serve as astronauts since the original Mercury Seven in 1959.

The astronaut candidates will report for duty at JSC in January to begin two years of training. Astronaut candidate training falls into five major categories: operating and maintaining the International Space Station‘s complex systems, training for spacewalks, developing complex robotics skills, safely operating a T-38 training jet, and Russian language skills.

Upon completion, missions may involve performing research aboard the International Space Station, launching from American soil on spacecraft built by commercial companies, and deep space missions to destinations including the moon on NASA’s Orion spacecraft and Space Launch System rocket.

Marcos Berríos

A native of Guaynabo, Puerto Rico, Berríos, 37, is a U.S. Air Force major and test pilot who received his bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from MIT and a master’s degree in mechanical engineering as well as a doctorate in aeronautics and astronautics from Stanford University.

A distinguished pilot, Berríos has accumulated more than 110 combat missions and 1,300 hours of flight time in more than 21 different aircraft. “As a test pilot I really I truly believe in the human space exploration mission, and I would love to contribute to the development of the new vehicles that are going to take us to the moon,” he says.

At the time of his selection as a NASA astronaut candidate, Berríos served as the commander of Detachment 1, 413th Flight Test Squadron and deputy director of the CSAR Combined Task Force. While a reservist in the Air National Guard, Berríos worked as an aerospace engineer for the U.S. Army Aviation Development Directorate at Moffett Federal Airfield in California.

“I’ve always wanted to be an astronaut,” he says. “When I was five or six, I wanted to travel to nebulas and other galaxies. The book ‘Ender’s Game’ was probably the book that certainly helped continue that inspiration for exploring space.”

A voracious reader of astronaut autobiographies, he decided to emulate them by getting his PhD and joining the military.

Berríos says that MIT first began preparing him for the rigors of being an astronaut during the “hours and hours and hours of trying to finish all the problem sets that we had to do it in a week. I think that discipline alone absolutely prepared me to handle or tackle anything else that that came my way.”

“I went into mechanical engineering because I wanted to build things,” he adds. “I wanted to use my hands. I took 2.007, a class I would Google when I was in high school — that class alone motivated me to want to go to MIT. I think those hands-on skills are extremely important for astronauts. On a space station, we do need to, you know, fix the toilet, we do need to maintain that vehicle in space, and so I think the hands-on skills, the problem-solving skills that I got from studying at MIT will be extremely helpful.”

Christina Birch

Birch, 35, grew up in Gilbert, Arizona, and graduated from the University of Arizona with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics and a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry and molecular biophysics. At MIT she worked in the Niles lab in the Department of Biological Engineering, gained skills in engineering and communication, and was active on the MIT cycling team.

After earning a doctorate in biological engineering from MIT, she taught bioengineering at the University of California at Riverside, and scientific writing and communication at Caltech. But she was pulled back to cycling competitions, and left academia to become a decorated track cyclist on the U.S. National Team, and at one point was bound for the Olympics. While she was on hand to support her Olympics teammates in Japan this summer, she also lined up her second interview with NASA.

As a professional athlete track cyclist, her training regimen will come in handy. “My training is going to be very varied and require a lot of different physical skills, so some of the things I’ve already started to do is finally work on my upper body, which we neglect as cyclists. So, I’m trying to work on shoulder strength and flexibility grip strength preparing for a spacewalk training in the neutral buoyancy lab.”

“Being an astronaut was always a dream sort of in the background, but I really don’t think it was until I was working in the lab doing experiments in biology, bioengineering, and chemistry. I saw what was going on in the in the Space Station and seeing similar experiments being done up there, and I said, ‘Hey you know, this is a skill set that I have. Maybe I have other things I can contribute.’”

“It’s still sort of sinking in, the fact that I’m sitting here in the flight suit,” she says. “I’m really excited to be training in the T-38 jets, because half my class are incredible pilots, so I can’t wait to fly with them.”

Will she be the first woman on the moon? “I don’t need to be the first, I just want to be a part of this program,” she says.

She hopes to do some bioengineering experiments in microgravity, such as tissue engineering applications. “On Earth under gravity, cells are limited by their own weight, and their sizes are limited, so they can usually only grow in two dimensions, where in space without Earth’s gravity, they expand more readily.”

Christopher Williams

Hailing from Potomac, Maryland, Williams, 38, graduated from Stanford University in 2005 with a bachelor’s degree in physics and from MIT in 2012 with a doctorate in physics with a focus on astrophysics.

As a kid, he remembers drawing the space shuttle and watching shuttle launches on TV. “That kind of instilled in me both this passion for space exploration but also this interest in science,” he says.

In between Stanford and MIT, he took a gap year to work as a radio astronomer at a naval research lab in Washington and to research supernovae at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. He also worked on the side as an EMT and as a volunteer firefighter, skills he brought with him to MIT. “Being an EMT helped me learn how to stay calm and manage pretty challenging and difficult situations, but also to give back to the community that I’m a part of.”

At MIT, he focused on astronomy and astrophysics. With his adviser, Jackie Hewitt, they worked on building the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) to look at the very early universe to understand how the first stars and galaxies formed and what that did to the evolution of the universe.

And yet… “I kind of had that astronaut dream still blowing away in the back of my mind and getting to interact with some of the MIT astronauts was a great way to kind of keep adding that flame,” he says. “The building that my office was in, every morning I’d walk in and see a picture of Ron McNair on the wall that was pretty inspiring to see, and knowing that he’d come from MIT as well, I’d think about that.”

After MIT, he took a left turn, applying his physics knowledge to medicine.

Williams is a board-certified medical physicist who completed his residency training at Harvard Medical School before joining the faculty as a clinical physicist and researcher. He most recently worked as a medical physicist in the Radiation Oncology Department at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. He was the lead physicist for the Institute’s MRI-guided adaptive radiation therapy program, and his research focused on developing image guidance techniques for cancer treatments.

Williams also met his future wife, Aubrey Samost-Williams ’10, SM ’15 at MIT, and they now have a 2-year-old daughter.

“It’ll be kind of a unique and interesting background that I can hopefully bringing contribute to the space program, because I hopefully bring in both my astronomy and astrophysics background, but also knowledge of radiation and medicine,” Williams says.

He still hopes to continue his graduate work at NASA. “The moon is actually a great place to put a low-frequency radio wave around, because it can shield you from some of the radio noise from Earth and that could allow us to probe some of the universe in a range of the electromagnetic spectrum that we’ve never been able to do before.”

The NASA Artemis Generation is an initiative to put the first woman (and next man) on the moon by 2024. The first class to graduate under NASA’s Artemis program, in 2020, included three aeronautics and astronautics alumni, Raja Chari SM ’01, Jasmin Moghbeli ’05, and Warren “Woody” Hoburg ’08. Former Whitehead Institute research fellow Kate Rubins, who was selected as a NASA astronaut in 2009 and had served as a flight engineer aboard the International Space Station, also joined the team.