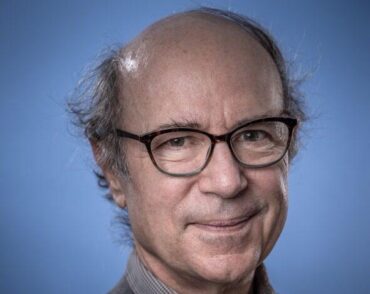

Prof. Edmund Bertschinger shares his perspective on the importance of science activism and diversity in STEM

Meet Edmund Bertschinger, a professor of both the physical and social sciences

03/22/2024 (11:04 AM): In a previous version of this article, the authors wrote that the Women’s & Gender Studies program was a department, when it is instead a program. To further clarify this distinction, Bertschinger taught a class in “WGS and STS,” not “SHASS and STS.” These errors have now been rectified to reflect this.

—

Professor Edmund Bertschinger is both an astrophysics professor who researches gravitation and chaotic dynamics and an affiliated faculty member in the Women’s & Gender Studies (WGS) Program. Bertschinger served as MIT’s inaugural Institute Community and Equity Officer from 2013 to 2018. The Tech sat down with Bertschinger to discuss his unique position at MIT and his work toward a more diverse MIT.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

TT: What made you interested in championing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) for STEM?

Bertschinger: It has always been an interest of mine, even going back to my college years. I was a college student when the women’s movement was becoming very active in society, which happened to a lesser extent in universities in STEM fields. I was a member of the National Organization for Women in the 1970s, one of the pioneering organizations championing the Equal Rights Amendment. In graduate school, I was a nuclear disarmament activist in the early 1980s.

After earning tenure at MIT in 1992, it became clear to me that there are deep-seated inequities in STEM and that I could not remain complicit in perpetuating them. I realized that I had been socialized in an oppressive masculine culture and was beginning to absorb the traits that I found upsetting in others. Showing no weakness, working harder than is healthy, putting work before personal life, being hypercompetitive — these traits have been shown by sociologists to correlate with toxic workplace cultures.

It took me years of service work and self-examination to understand the role of culture and gender. Once I did, it was clear that I needed to be in WGS. My primary appointment is in physics, but most of my research currently is in education and social change.

During the last decade, I’ve marched with students in Black Lives Matter protests, advocated for graduate student unionization, and helped organize a protest in Stata that would likely violate MIT rules if it were held today. More recently, I’ve become a scholar of social change. I teach Science Activism: Gender, Race, and Power (WGS.160), a class based on case studies of scientists and students using activism to drive change.

I was a first-generation, low-income student in college. Even though I had skin color and straight privilege that gave me advantages, many times, I felt like an outsider. Being a child of an immigrant mother, who had an eighth-grade education and didn’t speak English, was also a factor for me.

Having said that, I don’t think that the choice to participate in DEI, for me anyways, was entirely a matter of identity. It was ultimately a matter of where I could be most helpful and impactful in the world.

TT: You’ve been part of MIT for a long time. How would you describe MIT’s position regarding social issues and inclusivity, and how the Institute has evolved?

Bertschinger: Through teaching a course and science activism in WGS and STS, I’ve dug into the history of MIT and other universities, around their impacts in the social areas. MIT is a STEM-focused institution — its values are on learning, technology, and science. So it’s surprising to a lot of people that, at times, it has been a leader for social change, particularly related to DEI. I’ll mention three times in its history when MIT has been highly impactful.

One was in the 1968-1969 period of antiwar protests across the United States. There was a lot of student-led activism. At MIT, there was activism by students and faculty in some of the departments, notably physics. Why physics? Well, it was because there were faculty who were involved in the Manhattan Project, or advised the US government and the Department of Defense on military matters. And they knew the power of technology to both defend a country and kill people. They were very concerned about the use of technology in the Vietnam War, and its potential, especially with the power of nuclear weapons. So faculty and students started something called the March 4th movement for March 4, 1969. MIT was a leader among universities in championing the role of scientists and engineers in pushing back against the military industrial complex.

The second is the diversification of the faculty by appointment at that time — relatively large numbers of women faculty, and Black or African American faculty. They were quite rare in the university in the late 1960s and 1970s. The MIT physics department was unique in the late 1970s, in having more than 5%, almost 10%, of its faculty being women. There were seven women faculty at one point in the department, and this was more women than the next 10 departments in national rank combined. In physics, it was really quite a remarkable thing.

This was due largely to the championing of a few faculty, particularly a faculty member named Vera Kistiakowsky. She was also the founder of MIT’s faculty newsletter, which has become an important voice for independent thoughts of faculty. For the African American faculty, MIT had several moments from the early 1970s until the 1990s. The physics department wasn’t unique in having several black faculty members. Other departments were starting to appoint African Americans as well. But nationally, it made quite an impact. A lot of the first PhDs given to African Americans in physics came out of MIT, including Shirley Jackson, a very famous woman who later became the president of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. She was the second African American woman to receive a PhD in physics across the nation, and the first from MIT.

My final example is the 1999 Women in Science Report, led by biology professor Nancy Hopkins and other women faculty in science. This was a national model for empowering women faculty, not just in STEM, but broadly in higher education. It led to a lot of similar efforts at other universities.

MIT is a place, for most of its history, that has devolved a lot of the authority to faculty, as opposed to having a very powerful central administration. That has led to a culture of entrepreneurship and innovation. Of course, we are well-known in engineering. But it’s not only engineering. It’s not only the School of Management. The social context of MIT empowers individuals to make changes and improvements.

I would say that there’s a kind of a culture of educational practice that many of us hold without organizing something highly visible. In fact, a lot of change happens at the grassroots level, driven by individual actors who draw ideas and inspiration from one another. I think that contrasts with some other larger universities, where there’s a sense that the individual really can’t make much of a difference. Things are so centrally organized, that you have to work entirely within the system to affect change. Activism is more likely to occur when people think that they can make a difference.

TT: How do you foster an environment conducive to inclusion? You’ve written in the past that calling MIT a meritocracy is harmful. Could you elaborate on what you meant by that?

Bertschinger: An inclusive classroom is one in which the instructor values each student as an individual with unique strengths and experiences. This is achievable even in a large class. A key is to recognize that what affects students outside the classroom affects them in class, too.

I’m challenging other faculty about how we can be truly inclusive in our classrooms. Beneath the levels of organizations and structures, the level of the individual classroom is where it matters.

For the 2015 ICEO report that I wrote, I made a list of what I thought were MIT’s core values. One of them was that MIT strives to be a meritocracy at its best. You don’t get to MIT because of having a wealthy relative; you have to earn it. MIT doesn’t award honorary degrees and doesn’t have legacy admissions. Those are meritocratic, and I see nothing wrong with them. I think they’re outstanding; they advance the possibilities for equality and for people to achieve what they can.

In the report, I made a provocative statement, that calling MIT a meritocracy can be harmful. What I mean is, we sometimes think that’s enough. That all we have to do is bring in “the best” students. We have a level playing field, and therefore people will succeed based entirely on their own merits. That’s the usual argument for a meritocracy.

The problem with it is that there never is a purely level playing field. What counts as merit? Is it a GPA? Is it landing a job at Google? What about the student who wants to improve the quality of life in their hometown?

Do we value helping others? Do we value collaboration? We say that we do. How do we measure that? I think that it’s intellectually sloppy to say that MIT is a meritocracy, to pat ourselves on the back without realizing that meritocracy misses so much of the story of people’s experiences.

Ever since I started on the faculty here in 1986, I realized quickly that my students’ collective impact would vastly exceed my own. That motivated me to help others develop their skills and to improve my mentorship skills. The COVID-19 pandemic provided a need and opportunity to train large numbers of peer mentors to help hundreds of MIT students each semester, and we’re going strong four years later. This has been one of the most fulfilling projects of my career.

For example, the instructor in a classroom has power over what the student is assigned, and they’re grading to communicate a sense of the values that they hold about inclusion, about support, collaboration, and encouragement. I’ve started my classes with a syllabus statement of what it means to have an inclusive classroom:

“As participants in this class, each of us commits to supporting an inclusive classroom environment where everyone feels welcome to participate and contribute to our learning community. We agree to listen and speak respectfully and to expect to be both challenged and valued.”

What does this mean in practice? It means setting up the curriculum in a way that fosters collaboration, group learning, and respect. It means having discussions, where you provide the students with grounding, establishing a vessel of psychological safety where people can share their feelings. That’s not an easy thing to do; it does not usually happen in a STEM classroom. I strive to do that, at least in my humanities class, and I think to a large extent we succeed there. I’d like to see that kind of culture brought more increasingly into the STEM classes as well.