Scientists as engaged citizens

In a new MIT class, students explore how STEM researchers bring their knowledge to major societal issues.

The classroom in fall 2020 looked very different than it did when WGS.160/STS.021 (Science Activism: Gender, Race, and Power) ran for the first time in 2019. Zoom and virtual breakout rooms had replaced circles of chairs, but the shifts made the class no less immersive and urgent for its students.

In fact, the pandemic context made the core questions of this new survey class all the more vivid: What roles have U.S. scientists and technologists played as activists in crucial social issues and movements following WWII? What are their motivations, responsibilities, and strategies for organizing? What is their impact?

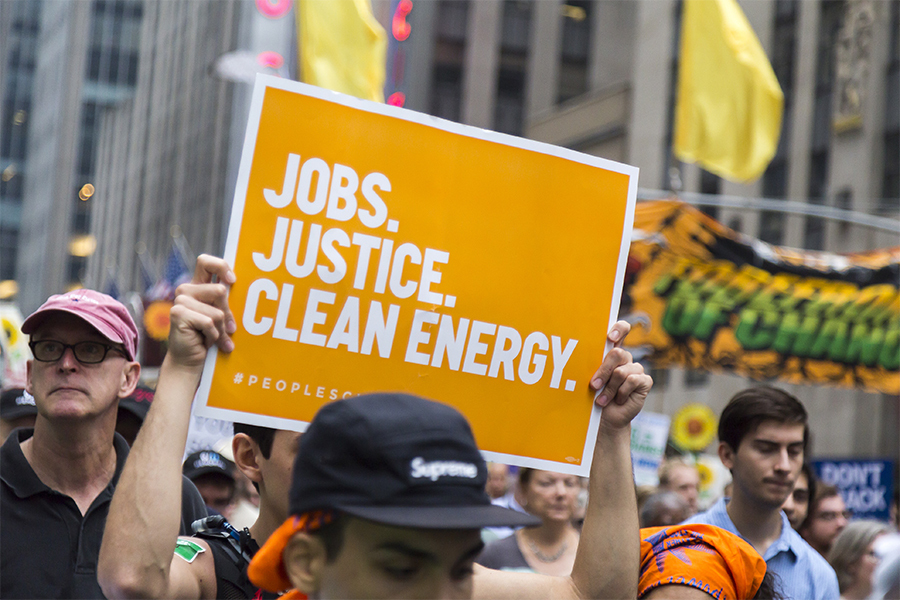

Scientists have been on the front lines of active citizenship and policy engagement in recent years in very visible ways — in the People’s Climate Movement, in controlling the global Covid-19 pandemic, and in testimony about biases in facial recognition in Congress, to name just a few.

As students in the Science Activism class have learned, this engagement isn’t a new phenomenon. There is a long history of scientists championing important issues, policy positions, and public education by contributing their scientific knowledge and perspectives. Case studies in this course include the civil rights movement, the nuclear freeze campaign, climate science and action, environmental justice, Vietnam War protests, the March 4 Movement at MIT, and advocating for gender equality in STEM fields.

Reflecting the layered and intersecting issues this class explores, it is listed in both the Program in Women’s and Gender Studies (WGS) and in the MIT Program in Science, Technology, and Society.

From the research bench to the policy table

Scientific knowledge is now critical for public understanding and sound policy for most of today’s most critical issues — from climate to human health to food security — and MIT students are eager to understand how their works interact with social realities and how they can lend their expertise to advancing better conditions and policies.

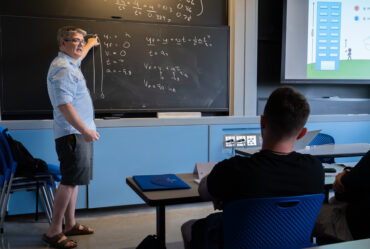

“The class was informed by the increasing efforts by scientists to engage in public policy not only at the ballot box, or by providing testimony,” says Ed Bertschinger, professor of physics, who led the initial class in 2019 as well as the 2020 class. “More scientists are also taking up causes of activism. That’s been true at MIT and around the country.”

As a faculty affiliate of the WGS program, Bertschinger notes that science has never been purely objective or detached from society. “Activism is a way for groups with less power in democratic societies to have their voices heard in order to effect change,” he observes. “Scientists can no longer take for granted that their results speak for themselves.”

Bertschinger recalls that his first experience with activism was in graduate school, in the 1980s, when he served as an organizer for the Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign. “I was following the lead of an MIT group,” reflects Bertschinger, “including scholars such as the late Randall Forsberg and Philip Morrison, who were leaders in the nuclear disarmament effort in the U.S.”

Bridging the gap

His students now are similarly broadening their areas of academic interest into awareness of the context, impact, and influence their respective fields have in society.

For Eleane Lema, a senior majoring in chemistry/biology and minoring in anthropology, the draw of Science Activism came from a sense of disconnection between her academic life as a scientist and her drive to make a positive social impact. The class subjects dovetail with her explorations of environmental justice and the unequal benefits and harms scientific change has for different communities.

Taking MIT’s mission “for the betterment of humankind” to heart since her first year at the Institute, Lema seeks ways to combine her technical education and her wish to engage in meaningful social work. This past summer, for instance, she had a health policy internship through MIT’s Washington Internship program, a longstanding initiative led by Charles Stewart III, the Kenan Sahin Distinguished Professor of Political Science, and founding director of the nonpartisan MIT Election Data and Science Lab.

“WGS.160 is an opportunity to learn about the positive influences scientists have made in addressing the world’s biggest challenges,” says Lema. “By bridging science and social issues, this class shows us real, practical ways to embody MIT’s mission to serve humankind.”

A duty to learn

Emily Condon, another senior in the class this fall, also sees WGS.160 as an opportunity to understand her own social responsibilities as a scientist. “With the recent Black Lives Matter movement events and the current political climate, I felt a responsibility to educate myself on what I, as a student of science and engineering, could contribute to ending violence and discrimination against Black communities.”

“The most profound idea that I’ve learned in this class is that science is not entirely objective,” reflects Condon. “There are always biases about what science implies or what scientific problems are important to study. Providing more spaces for BIPOC scientists to direct the course of research is essential to diversifying perspectives and approaches to science.”

Condon followed the tangible effects of such biases as she studied the material impacts of climate change and its roots as a social, as well as a scientific, problem. “Underserved communities are disproportionately impacted by the negative effects of climate change, and recognizing that can help scientists and engineers direct efforts to aid the people in those communities.”

For senior Kate Pearce, who is majoring in computer science and biology with a minor in math, the class is a chance to connect her longtime interest in science and activism. It has also given her a greater sense of continued agency over her own technical projects by learning how scientists have been able to anticipate and influence how their innovations will impact people, rather than simply allowing political and economic systems to determine how their work will be used.

The class, in both runs to date, has been composed primarily of MIT undergraduates focused on technical fields.

Like their professor, the students come to the WGS program as interdisciplinary thinkers, pursuing a fuller and more nuanced sense of their work’s place in a volatile world. The program is designed to enable just that understanding — drawing on expertise across the Institute, from physicists to philosophers to poets, to provide analytical frameworks for the examination of gender, race, ethnicity, class, and sexuality — and how these aspects of human identity intersect with the life and issues of society.

“The feminist lens of Science Activism really intrigued me,” Pearce adds, “especially as applied to how science and social change are motivated and executed.”

An active MIT history

Topics in Science Activism take a broad view of recent decades, examining Vietnam War protests by scientists, genetic engineering, and the birth of modern environmentalism in the United States. There is a special focus on activism at MIT in particular, from the 1960s to present, including the March 4 Movement.

That movement began in 1969, when research and regular teaching at MIT slowed as students, faculty, and staff paused to protest the war in Vietnam and the Institute’s links to the military. Similar themes echo to the present day, with students, faculty, and staff opposing military solutions to international conflicts and broadening MIT’s engagement into social and economic justice.

For Lema, the course has also provided insight into what successful activism looks like in projects like bringing awareness to the climate crisis. “MIT has played an integral role in the history of science activism, and I hope every MIT student gets the opportunity to learn about this history and discover how they can become activists for causes they are passionate about.”

Joining the conversation

Like many of MIT’s humanistic courses, Science Activism is discussion-based: students build a foundational understanding from assigned readings and come to the classroom (live or virtual) prepared to debate and discuss. Guest speakers, such as Harvard Medical School Professor Jon Beckwith, who has led a Harvard University course focused on activism and the life sciences, broadened and deepened the conversation in the class’s first iteration by adding the perspectives of specialists in different disciplines.

This year the class welcomed via Zoom a number of new guest speakers, including Jin In, an advocate for women’s empowerment; Arwa Mboya, a former research assistant at the MIT Media Lab; and Steve Penn, a prominent MIT activist of the 1980s and ’90s. As a discussion-based class, the students’ insights are the engine of the class experience, and Bertschinger dedicates the majority of class time to breakout rooms so each student has a chance to thoroughly engage with ideas and questions.

“I have been so impressed by the passion and insight that my peers in this class provide,” says Pearce. “Since people are so engaged and passionate about these topics, the breakout rooms always lead to wonderful discussions, and we must struggle to end as the timer ticks down.”

For instance, the climate crisis — one of the foremost issues of the students’ lives — inspires intense, far-ranging conversations as class members trace the roots of environmentalism and think together about how best to respond to the multi-faceted crisis. The students’ experience gives the course an ever-expanding horizon as students’ insights widen discussions around intersectional equality in the sciences and in society.

“It was a great pleasure to teach the class last year; I learned a lot from working with the students and from developing case studies,” reflects Bertschinger. “It’s important for the MIT community to pay attention to the activism on campus — and to help our students develop the wisdom and the capacity to use their voices to the fullest effect in the world.”

Story by MIT SHASS Communications

Editorial team: Alison Lanier and Emily Hiestand